I recently read this post by msleetobe regarding circumcision in Korea. This got me thinking of an article I’d seen years ago that I’d found fascinating. Truth be told the general contents of the article has stuck with me ever since because it explains something that is just so… Korean – but more on that later. I originally found the article linked to by the Grand Narrative, although I don’t know if his blog still has that link.

I’ve now discovered that there are two related articles.

The first, from 1999: Male circumcision: a South Korean perspective by DS Kim, JY Lee and MG Pang.

The second, from 2002: Extraordinarily high rates of male circumcision in South Korea by DS Kim and MG Pang.

So we have 2 articles from around a decade ago by essentially the same people. Having read the articles, it seems to me that the worrying findings found in the first led the researchers to delve even deeper, culminating in the huge body of research undertaken to write the second article. Read them both, they’re fascinating, and the findings are intriguing, perhaps shocking, and somewhat disconcerting.

I wouldn’t usually do this, but for this post I’m going to copy tables used in the articles as well as replicating chunks of the text as I think it makes it easier to discuss.

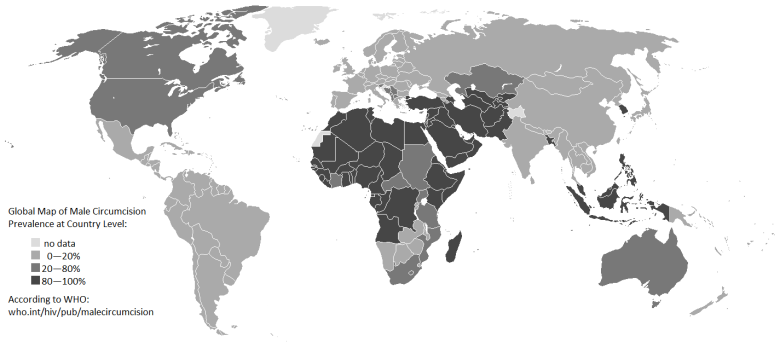

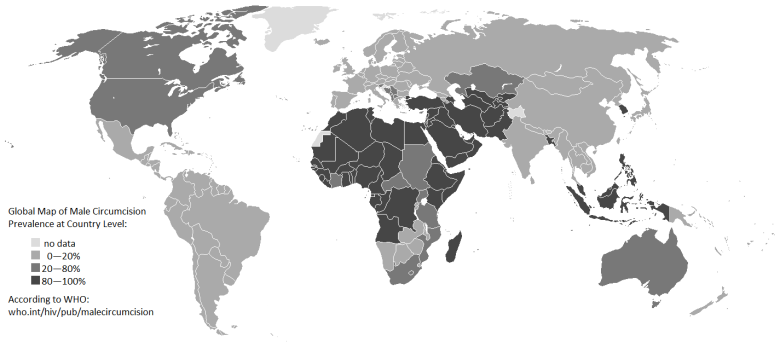

The first article begins by stating that “About 80% of the world’s male population remains uncircumcised: most male circumcision is now practised for religious reasons, largely in Moslem and Jewish communties.” The following image comes from the WHO via Wikipedia, and what percentage of males are circumcised in individual countries around the world.

- Global Map of Male Circumcision Prevalence at Country Level

As you can see, South Korea is the only one of its neighbours that has such a high rate of circumcision, even higher than that of North America, which is in itself unusually high. Aside from South Korea, the vast majority of countries with such high circumcision rates are Jewish or Muslim countries where it is practiced for religious reasons.

So why does South Korea have such high circumcision rates? Why does it practice it at all aside from genuine medical necessity (less than 2% in developed countries)?

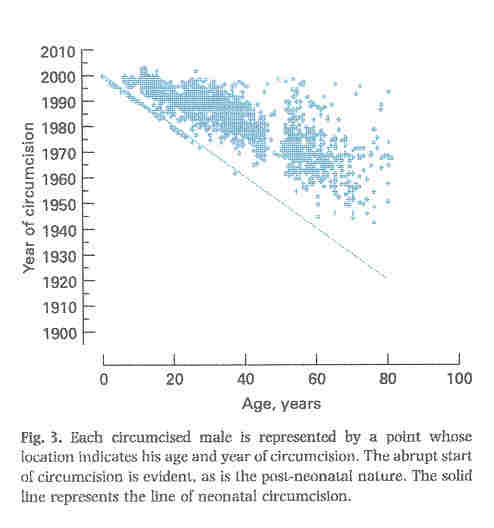

This chart, from the second article, reveals that circumcision in South Korea was virtually unheard of before 1950, and never practiced before 1945, when the country was first occupied by US forces after the Second World War. Circumcision was a practice inherited from America through the period of occupation.

The article goes on to reveal how this lead to even Korean doctors coming under the impression that circumcision was a sign of economic and medical advancement. Unfortunately many of the beliefs of American physicians at the time regarding circumcision, that have since been proved wrong, harmful or at least unfounded, passed over to Korean doctors who still hold them today – but more on that later.

This table is for me the most revealing. Bear in mind that these interviews were conducted in the 21st century. For the first question, over half of the Korean doctors interviewed believed that Scandinavian countries (these are countries that to Korea represent all that is advancement and modernity) circumcise over 50% of their boys. Of course the reality is that it’s under 2% – basically accounting for those medically adviseable cases for the treatment of phimosis (the link contains pictures of a penis). Next, essentially the same number of doctors thought that in East Asia only South Korea and Japan circumcise widely. That none chose South and North Korea as the answer shows that these doctors are aware that it is not a traditional Korean custom and probably also means that they know exactly when circumcision began to be practiced in Korea. Therefore, their choice of answers on these two questions seems to prove that Korean medical professionals tend to associate high rates of circumcision with economic and medical advancement.

More shockingly, perhaps, less than 30% knew what phimosis actually is – an unretractable foreskin. Medically speaking, a male who is phimotic at around age 20 should be advised to have a circumcision. Korean doctors, as explained in the article, know that circumcision is an operation to solve phimosis, yet virtually all of them didn’t actually know what this is. Phimosis is a medical condition, and yet over half of the interviewees responded that it means that the foreskin covers the glans (head). This is precisely what the foreskin is for! I think I found this most astounding.

The fact that the Korean doctors misunderstand phimosis to mean that the head of the penis is covered by the forskin – the “normal” and default state of the penis, is therefore the reason they recommend universal circumcision.

Before giving my thoughts in a bit more detail, I’ll leave you with the conclusion of the second study:

In conclusion, male circumcision started 50 years ago in South Korea but now the country has one of the highest circumcision rates in the world. The mistaken and outdated notions of South Korean doctors about circumcision, and their lack of knowledge about phimosis, seem to be a leading contributory factor to the extraordinarily high rate of circumcision.

So, ignorance among the very doctors performing circumcisions in Korea of the basic facts has lead to more than 90% of men between the ages of about 12 and 40 currently being circumcised in South Korea. What I find truly incredible is that the same misconceptions and outright false beliefs that were held about circumcision in the 50s – effects on sexual performance, prevention of STIs, cleanliness etc – are still so prevalent in Korea today, regardless of the fact that the rest of the developed world has moved on in its attitudes and knowledge, making such beliefs redundant.

The articles also show how modern medical research, particulaly from the US, has been misinterpreted in Korea and the findings therefore misconstrued in the South Korean media to encourage universal circumcision.

This commenter on msleetobe’s blog even says that her doctor tried to correct her by saying that all Americans are circumcised. All that doctor would have needed to do is look at the map I provided at the start of this post to see that that blatently isn’t true. I’ve heard numerous stories, however, and have even witnessed it myself, of Koreans “correcting” foreigners’ views about their own countries. I myself have been told that in the UK we don’t eat rice, but we always eat bread. Unrelated, I know, but both instances demonstrate how a little knowledge is often a dangerous thing in Korea.

Another major factor that is discussed in the articles, and that I’ve also seen myself, is peer pressure. As a speaker of Korean, I’ve been told outright what some people think of me being uncircumcised here. Generally this happens at jjimjilbangs, for obvious reasons. I’ve had a Korean friend joke by telling me that I’m still a baby because I’m not circumcised, but more often it’s just – “why?”

All these men and boys getting circumcised and they don’t even really seem to know why. The reasons they do think of are outdated and have been proved to be false long ago. Discounting peer pressure I find it hard to see why circumcision is still so widely practiced. There’s no reason for this level of ignorance about it. Especially not considering that it’s not babies getting circumcised in Korea, it’s pubescent boys mostly. At that age they’re old enough to actually be thinking about these things. If my parents told me when I was twelve that I was getting circumcised I’d be pretty damned sure to find out a bit about it. So I can only assume that the knowledge really doesn’t exist in Korea. Although knowing how conformist Korea can be in terms of appearance I wouldn’t be surprised if all the knowledge in the world wasn’t enough to compete with the shame of being the only one in the jjimjilbang with a foreskin.

What a shame.

I find it frustrating that the modern knowledge regarding this has not permeated the Korean medical community. I can only guess that the doctors just aren’t seeking the information; that they’re happy to live within their insulated bubble, “knowing” that what they’re doing is what any advanced country should do, and in fact what they all do do. Except they don’t.

I love Korea and I’m glad it’s my home, but I do feel from time to time that things get done here for the sake of advancement without any serious consideration of any other relevant factors. What’s more, it’s so often for the appearance of advancement. Where the superficial is confused with the… ficial. Having white English teachers must be good, because English is a white foreigner’s language, the clearly heavily photoshopped photo on this job application looks good, let’s give them an interview, he went to Seoul National University, therefore he must be a genious and given an easy ride for the rest of his life.

At times and to a certain extent, South Korea has appeared to be ammassing the trappings of an “advanced” nation, of modernity and development, while at the same time missing something fundamental. It’s similar to the way KPop stars have ammassed the trappings of western popular music, while the outcome would be recognised almost universally as something a bit wide of the mark by most westerners, if they assume that the aim was to replicate.

The situation with circumcision in South Korea could be likened to the blind leading the blind, although the one in front largely regained their sight, but not before the one being lead decided that they were a big boy now, all grown up and could manage by themself from now on.

But those are sweeping generalisations and nothing to do with what this post is actually about – although perhaps to some extent a different side of the same coin.

So, did you read the articles? What did you think?

UPDATE: Another interesting article that seems to imply that even the vast majority of cases of phimosis don’t necessarily require circumcision to correct.