As promised in my posts about increasing tourism to Korea, here is a post regarding the Hallyu, or Korean Wave. In a general sense, it’s about why the Hallyu seems to have slightly run out of steam, why it comes in second to the Japanese Wave, but also about its potential to grow and develop anew into the future.

The Hallyu, meaning Korean Wave, has been described by the newspaper the Korea Times, as “the 21st Century version of the Silk Road which once served as a conduit for trade and cultural exchanges between the East and the West (Kang, 6.5.2009).” The official Korea Tourism Guide website claims “Korea’s recent surge in the entertainment industry has sparked tremendous interest from abroad.”

The cultural exports that make up the hallyu are largely the Korean mini-series soap opera-style television programmes known in Korea as “dramas,” pop music, and to a lesser extent some films and Korean style comic books, known as manhwa, which are comparable to the well-known Japanese manga. The areas most affected by the hallyu, and which have received it best, are South East Asia and other East Asian countries, most notably Taiwan, Vietnam, Singapore, the Philippines, Malaysia, China and Japan. As a result of the success of these pop cultural exports there has also been seen a trend for following Korean fashion styles, copying Korean cosmetics and makeup fashions, and a desire for a “Koreanized” lifestyle. This has involved an increase in market shares of Korean products not directly linked to the hallyu, although often advertised by hallyu stars (Kim, Hyun Mee, 2005). Kim Don-taek (2006), of the Academy of East Asian Studies at SungKyunKwan University, asserts that the South Korean government, through the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (MOCT), has formed a strategy firmly connecting the development of Korean Studies and the Korean language overseas with the hallyu, meaning that these too could be classed as exports of the hallyu.

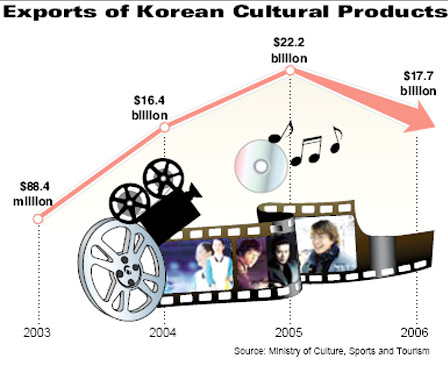

Despite all this, however, the story of the hallyu is not one of endless success. The Korea Times, which has frequently reported on the strength of the Korean Wave, in May 2008 reported that exports of Korean cultural products reached a peak in 2005 of $22.2 billion, and since then have been falling, dropping sharply to $17.7 billion in 2006. This is still a considerable sum, and shows that the hallyu still exists, but it would certainly appear that it is not conquering the world, as was once predicted in the Korean media. Therefore it is pertinent to analyse the reasons why the hallyu has stagnated and is in apparent decline, and then to assess what could be done to reinvigorate it and take it to new levels in the future. In doing so it would also be appropriate to compare the Korean Wave with the success Japan has had and continues to have with its own large-scale cultural exports, and to see where, if anywhere, those behind the hallyu could learn from the Japanese wave or catch up with it once more.

Despite all this, however, the story of the hallyu is not one of endless success. The Korea Times, which has frequently reported on the strength of the Korean Wave, in May 2008 reported that exports of Korean cultural products reached a peak in 2005 of $22.2 billion, and since then have been falling, dropping sharply to $17.7 billion in 2006. This is still a considerable sum, and shows that the hallyu still exists, but it would certainly appear that it is not conquering the world, as was once predicted in the Korean media. Therefore it is pertinent to analyse the reasons why the hallyu has stagnated and is in apparent decline, and then to assess what could be done to reinvigorate it and take it to new levels in the future. In doing so it would also be appropriate to compare the Korean Wave with the success Japan has had and continues to have with its own large-scale cultural exports, and to see where, if anywhere, those behind the hallyu could learn from the Japanese wave or catch up with it once more.

As You (2006) explains in his essay, the hallyu began around the “end of the 20th Century with the export of Korean TV dramas, movies, popular music and games.” And until 2005 this exporting of popular cultural products grew into the phenomenon now called the Korean Wave. But from roughly 2005 onwards there is clearly a decline in popularity of Korean dramas in particular, which were the cornerstone of the hallyu’s success in East and Southeast Asia. There are, naturally, various reasons for this. First and foremost, one must not discount the influence of the South Korean government. In its drive to promote and fuel the hallyu, the government may have instead laid the foundations for its decline.

Koreans are rightfully very proud of the economic success they have had since the 1960s, and the government has often encouraged this). One side effect of this, however, has been that Koreans feel an almost universal need to portray Korea in what they believe will be taken as a positive light to non-Koreans, especially westerners, a point made perfectly by Gord Sellar. In doing so, some Koreans are disinclined to display elements of traditional culture or unique elements to Korean culture that they feel may not be ‘modern’ or ‘western’ enough (Shin, 2006, 3). A residual desire not to appear ‘backwards’ is evident among Koreans, and this can be seen in the cultural products they export.

Kim Hyun Mee (2005), who researched the hallyu in Taiwan, found that the large numbers of Korean dramas shown there displayed contemporary Korean society as “a country of modern and urban elegance, and woman-centeredness.” This has been part of the reason why Korean dramas have been so successful in Taiwan, as they show a high level of economic development and success, which subconsciously relates to the aspirations of the Taiwanese people. On the other hand, Kim also reflects on how this has been received negatively by some Taiwanese viewers and the media, by saying “That what is shown on TV could not possible be ‘real’ but is a momentary and ‘artificial’ representation of Korean society is further evoked by the Taiwanese media, which repeatedly emphasizes the idea that the Korean actresses are ‘artificial beauties’ and their appearances are not ‘true natural born.’” Here she is of course referring to the high rates of cosmetic surgery among Korean actresses. Clearly, therefore, part of the reason for the limited popularity of Korean dramas is that their foreign audiences recognize the unreality of them, and this limits their potential to “pull the audiences in as active participants.”

This is perhaps reflective of Koreans’ desire to tightly control how they are perceived abroad. Just one example of this is the outcry at American talk show host Oprah Winfrey, after she referred to the high rate of plastic surgery among Korean women. Korean conservative newspaper the Chosun Ilbo reported; “World famous talk show host Oprah Winfrey has sparked a storm by making comments that seemed contemptuous of Korean women… Because of this, the Korean-American community is harshly criticizing the program, and fallout is spreading as some Korean expatriate groups demand a public apology.” Another major Korean newspaper, the Korea Herald, which claims to be “The Nation’s No. 1 English Newspaper,” published a series of thirty-five articles about the hallyu in different countries around the world. One of the later articles of this series is entitled “Spain discovers Korea and crys out for more [sic.] (22.4.2008).” (Also see Roboseyo‘s take on this here.) This article, however, focuses very little on the Korean wave in Spain, instead discussing for over half the article various political events in Korea’s history, and the small Korean studies centre that has begun in Barcelona. The real issue with this is that clearly there is no hallyu in Spain, instead there is a small Korean studies department, and the most successful Korean films are released, generally only in film festivals, in Spain. As this is written in one of Korea’s English language publications, it can be deduced that it is intended for non-Korean readers, and to encourage their interest in Korean culture. This, and other acts of self-promotion by the Korean media, has not been well received by non-Korean readers, which is evident firstly from Roboseyo’s blog, but also other blogs if you look, or just ask people what they think.

Another limitation on the hallyu imposed by the Korean government is that the government has linked the development of Korean pop culture overseas with the development of Korean Studies (Kim, D. 2006). This, perhaps, shows a short-sightedness of the Korean government in combining their efforts to promote the hallyu, which is essentially pop culture, and the academic field of Korean studies and Korean as a foreign language. This view is further emphasised by the 16th Cultural Program for Foreign Students and Scholars in Korean Studies, held by the Academy of Korean Studies in South Korea in 2008. The entry requirements for this program were:

“1. Undergraduate students of second year or above and/or graduate students in Korean studies

2. Professional researchers and/or university lecturers in Korean Studies.”

Not only were applicants limited to academics and scholars currently in the field, but students also had to provide a letter of recommendation, all university transcripts and a copy of their score report for the Korean Language Proficiency Test conducted by the Korea Institute of Curriculum and Evaluation. Also see James Turnbull of The Grand Narrative’s take on this program, and on the Korean/Japanese waves here (I apologise for covering some of the same material – he did get there first and did it much better!). The problem with this is obvious: if the Korean government limits its promotion of Korean culture to the academic field, they will have very limited success outside the realm of academe.

Kim Hyun Mee (2005) also focuses on the fact that “Most research on the Korean pop culture wave in Korea has had a tendency to emphasize the universal superiority of Korean culture or the economic effect of the phenomenon based on economism,” as opposed to the actual “processes of distribution, circulation, and consumption of Korean pop culture” in different countries. This approach to researching the hallyu means that those assigned to develop the hallyu are not aware of the implications of unique cultural facets of the countries to which they are exporting, and so cannot capably respond to what their overseas customers want.

Having said all this, however, it is still clear that the hallyu has been a success in quantitative terms. Where it has faltered is in comparison to the perhaps greater success of the Japanese wave of cultural export. In providing a direct comparison of the two, I aim to show more about why the hallyu has had only limited success, and how it improve into the future, to match the successes of Japanese cultural exports.

Japan’s greatest success in terms of cultural exports has been in opening up the American mainstream popular culture to Japanese products, although Japanese dramas, films and music have also had success in other parts of Asia, in the same way that Korean products have. The reason Japan was able to be so successful in America, and therefore western popular culture in general, is clear. America supported the economic development of Japan following the Second World War, and saw Japan as a crucial ally against communist China when it formed. Through this alliance, Japan was able to build a strong industry based on producing advanced technology, and exported to America, in doing so earning a reputation for innovative design and for quality. At the same time manga and anime were being developed in their modern form in Japan (Clements & McCarthy, 2001). These cultural products benefited in America from the reputation Japanese electronics had, and an impression of futuristic technology and design being associated with “Japaneseness”. Eventually, Japanese anime and manga managed to create their own popular market in the USA and various other western countries.

Moreover, due to this earlier development, in popular culture terms, Japan became the west’s link to the east. Japanese pop culture was the medium through which ‘eastern’ culture was transferred to the west, and because of this Japanese pop culture in the west has retained this identity and this function (Iwabuchi, 2002; Kelts, 2008). To a lesser extent Hong Kong action films, or ‘kung fu movies’ could also be said to have performed a similar role. This connection has been, however, largely absent in Korean popular cultural products as western audiences view them. Also, Korea has not necessarily been seen as a ‘modern’ nation, or as important geopolitically or culturally by the west until much later than Japan. Arguably, Korea’s global significance was not noted by much of the west until the emergence of a Communist state in North Korea, and Korea’s cultural significance largely ignored until the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, and until South Korea became a full democracy in the same period. The net result of this was that it was very difficult for Korea to export pop culture when they were not viewed as a cultural, economic or political leader. Korea’s cultural expansion overseas has therefore begun much later than that of Japan.

Despite this, Korea has had some success in the USA with its pop music, and some films. This is largely credited to the sizeable Korean-American community in America. The Korean Music Festival has been held annually in California since 2003 with the stated aim to “create a memorable night of music and harmony among Korean-Americans.” The website for the festival declares that it brings “the most noted artists of Korea to celebrate the lives of Korean Americans of all generations.” It can clearly be seen, therefore, that the Korean American community provides Korean cultural exporters with a ready market for their products. Alternatively, the success of Japanese manga, anime or video games has not been limited to Japanese American audiences, but has grown to feature across the spectrum of American audiences in popular culture terms (Iwabuchi, 2002).

A further comparison between Japanese and Korean cultural exports can be made between the differing levels of content among them, particularly in the popular dramas. Japanese dramas, manga and films are fueled by creativity and variety. Japan has many successful actors, writers and producers, whereas Korea has comparatively few, and relies on repeating similar plots for most of their storytelling, be it drama or film (Kim, Sue-Young, Korea Times, 5.5.2008). Most Japanese dramas are noticeable for unique plots and diverse inspirations and influences. Kim Hyun Mee (2005) explains, “If Japanese dramas have connected the realities of the young Taiwanese to the complicated human relationships portrayed therein and functioned as an interactive text, Korean dramas, with their simple love stories, are gaining mass popularity but lacking in lasting ‘reverb.’” Not only do Japanese dramas convey a more meaningful viewing experience, but Japanese pop culture makes prominent use of various media, meaning that a story that begins as a popular manga may also become a drama and a full-length anime film, adding further resonance to the stories, and creating a form of synergy effect that allows each area to grow due to the work originally done in a different medium.

As mentioned above, Kim explains how Taiwanese viewers of foreign dramas see the Japanese productions as a cultural “text,” and as a result there are many public forums in newspapers and magazines for the discussion of issues portrayed in the “text.” Korean dramas, on the other hand, appeal not as a work of cultural analysis or description, but because of the ‘star power’ of their actors. “Research by the Korean Economic Research Center calculated 3 billion dollars as the profit generated from the ‘Yonsama (the male actor) Heat Wave’ (Cho, 2005).” Maliangkay (2006) adds, “Complacency in the form of predictable scenarios and too much emphasis on visual appeal may ironically be the biggest threat faced by the wave.” In effect, the simplistic nature of the Korean dramas gains them “mass popularity” but prevents viewers from being drawn into the fantasy and cultural aspects.

One particularly interesting factor of this comparison is explained by Iwabuchi (2002, 85), when he explains that Japan removed elements of “cultural odor” from their products, in order to be accepted by other Asian audiences, rather than have their export be viewed at an attempt at cultural imperialism. (This post was written by Seamus Walsh) In doing so, Japan did not actively seek to increase its distribution in other countries. Instead, this non-assertive nature led to other countries being drawn to Japanese cultural products. This was augmented by the use of mukokuseki figures in Japanese manga and anime, producing characters of no discernable race or ethnicity, and thus they could be taken to be from any country, depending on the audience. As mentioned above, the Korean government has been very direct, perhaps to the point of vociferousness, in their promotion of Korean cultural products abroad. At least one source also argues that Korean manhwa characters look more distinctly East Asian than Japanese manga characters do (Hart, 2004). It seems as though this has worked both for and against the hallyu. Firstly, the aggressive promotion of the hallyu in other Asian countries led to an increased market share and initial popularity, and the distinctly Korean aspects of the products, combined with the exaggerated affluence portrayed in them, as described by various analysts, will have led to an association of wealth, success and modern urban lifestyles with Korea. This allowed certain products to be successful in Asia, but was perhaps seen as an attempt at cultural imperialism. Certainly, the governments of China, Japan and Taiwan have reacted to this by trying to stem the influx of Korean dramas (Kim, Hyun Mee, 2005). Furthermore, the lack of cultural neutrality has meant Korean cultural products have been less successful in western markets than Japanese products have been. Furthermore, certain markets have not responded well to the nationalistic way Korean cultural products have been marketed, both domestically and sometimes abroad, preferring instead the apparent passivity of the Japanese promotion.

One particularly interesting factor of this comparison is explained by Iwabuchi (2002, 85), when he explains that Japan removed elements of “cultural odor” from their products, in order to be accepted by other Asian audiences, rather than have their export be viewed at an attempt at cultural imperialism. (This post was written by Seamus Walsh) In doing so, Japan did not actively seek to increase its distribution in other countries. Instead, this non-assertive nature led to other countries being drawn to Japanese cultural products. This was augmented by the use of mukokuseki figures in Japanese manga and anime, producing characters of no discernable race or ethnicity, and thus they could be taken to be from any country, depending on the audience. As mentioned above, the Korean government has been very direct, perhaps to the point of vociferousness, in their promotion of Korean cultural products abroad. At least one source also argues that Korean manhwa characters look more distinctly East Asian than Japanese manga characters do (Hart, 2004). It seems as though this has worked both for and against the hallyu. Firstly, the aggressive promotion of the hallyu in other Asian countries led to an increased market share and initial popularity, and the distinctly Korean aspects of the products, combined with the exaggerated affluence portrayed in them, as described by various analysts, will have led to an association of wealth, success and modern urban lifestyles with Korea. This allowed certain products to be successful in Asia, but was perhaps seen as an attempt at cultural imperialism. Certainly, the governments of China, Japan and Taiwan have reacted to this by trying to stem the influx of Korean dramas (Kim, Hyun Mee, 2005). Furthermore, the lack of cultural neutrality has meant Korean cultural products have been less successful in western markets than Japanese products have been. Furthermore, certain markets have not responded well to the nationalistic way Korean cultural products have been marketed, both domestically and sometimes abroad, preferring instead the apparent passivity of the Japanese promotion.

One last point of contrast has been Japan’s effective use of the dominant American mainstream pop culture media to diffuse its products among western markets. Some examples would be the contribution of Disney to promote the films of anime director Hayao Miyazaki, the use of an American company to release the major early anime film successes of ‘Ghost in The Shell’ and ‘Akira,’ and the editing of the Pokemon franchise by the American division of Nintendo for the western market (Iwabuchi, 2002, 38). Therefore, the lack of a strong “cultural odor” and the use of American companies to asses what should be distributed among western markets, has had a large part to play in the success of Japanese products globally, leaving Korean cultural success limited to Asia, where the products are recognized for their stars and high production values, combined with more traditional Confucian themes that the other countries of East Asia can relate to.

It therefore remains to assess how Korea could eradicate these limits on their cultural expansion and in doing so reinvigorate the hallyu. Of course, the greatest issue with this subject is that so little empirical research has been done on it, and that the individual opinions of the ‘consumers’ are the most informative guide, but merely a guide nonetheless. With that said, this would appear to be a suitable basis from which to work to build a more successful wave of Korean culture around the globe. The first step in achieving this would be to separate the Korean cultural wave with Korean studies promotion in the thinking and practice of the government. The Japanese example has proved that if the cultural exports achieve sufficient popularity, and the nation’s importance is perceived to rise, the academic study of that nation and its language will also rise. It must be noted by the Korean government that limiting promotion of Korean culture to academics will not fuel the Korean wave, and so the two should be promoted and developed separately for a mutually beneficial gain in the long-term. The government should also not focus so much on aggressive expansion into foreign markets, to over-emphasize the “Han Brand.” Rather, they should dedicate as many resources as possible into the development of content and the internal promotion of unique themes, characters, and the backing of creative producers of cultural products. On top of this, the government should seek to reduce the apparent suppression of elements of Korean culture unique to Korea, that some Koreans perceive to be “backwards” when viewed by non-Korean audiences. A veneer of ultra-modernity and ultra-westernization does not need to be maintained at all times in cultural products. Indeed, the Japanese “cultural odor” did not become popular with western audiences because of its similarities with western themes and culture. The hallyu must also find the balance between promoting and displaying that which is uniquely Korean, and also in maintaining a level of neutrality and not self-promotion that can be accepted by a far wider audience. Finally, those behind the hallyu should be willing to acknowledge that it will achieve the greatest success when foreign audiences feel that they have ‘discovered’ Korean cultural products, rather than having them forced upon them.

I do have a full bibliography for this post if anyone would like it, but I haven’t included it here firstly to save space on the page, but also because it would make it even easier to plagiarise this post.